Ireland's Tragic Secret: Unearthing the Truth of the Tuam Mass Grave

Ireland's Tragic Secret: Unearthing the Truth of the Tuam Mass Grave

In the quiet town of Tuam, County Galway, a dark chapter of Irish history is finally being brought to light. For decades, a nondescript patch of grass, now adjacent to a children’s playground, held a terrible secret: the unmarked graves of hundreds of infants and children who died at the St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home. Operated by the Bon Secours Sisters between 1925 and 1961, the institution housed thousands of vulnerable women and children, many of whom were ostracized by society for falling pregnant outside of marriage.

The sheer scale of the tragedy was unknown until 2014, when amateur historian Catherine Corliss uncovered evidence suggesting a mass burial site, possibly within a former sewage tank. This revelation has led to a painstaking two-year excavation, commencing this week, to uncover the full extent of the horrors that transpired within St Mary’s walls. The unearthed remains are believed to be from the period the home was operational, with records indicating at least 796 children died within its confines. For survivors and their families, this excavation represents a long-awaited step towards truth and accountability.

The legacy of St Mary’s has cast a long shadow over the lives of those who passed through its doors. PJ Haverty, who spent his early years in the institution, described it as a “prison.” He recounted the profound stigma faced by the “home children” in the wider community, being segregated even during school playtime. This social ostracization, a constant reminder of their perceived illegitimacy, left indelible scars that have persisted throughout their lives.

Catherine Corliss’s journey into uncovering this hidden history began as a personal quest to explore her family’s past. Her research into St Mary’s was met with a surprising lack of records and even suspicion, fueling her determination. A crucial turning point came from a cemetery caretaker, who guided her to the site where the home once stood. There, near a children’s playground, a grotto now stands above what is believed to be the burial site. A story from the caretaker about boys discovering bones in a collapsed concrete slab in the 1970s, and a subsequent cover-up, added a grim layer to the mystery. While earlier records pointed to famine-era burials, Catherine’s meticulous cross-referencing of maps and death records revealed a more disturbing truth: the “sewage tank” marked on older maps was likely the final resting place for hundreds of infants who died at the home, their deaths unrecorded in public cemeteries.

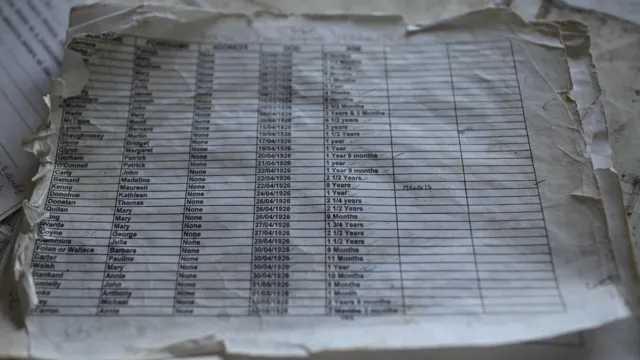

The scale of the tragedy became starkly apparent when Catherine obtained a list of children who had died at the home, revealing 796 names. Her findings, which gained international attention in 2014, were initially met with disbelief and hostility in her hometown. However, the testimony of Mary Moriarty, who lived near the site in the 1970s, provided chilling corroboration. Mary recounted falling into a hole near the grotto, only to find herself in a dark space filled with “hundreds” of “little bundles” wrapped in decaying cloth, packed in rows. Her realization that these were babies, mirroring the bundled infants she received from the nuns after her own child’s birth, brought the horrific reality into sharp focus.

In 2017, a government investigation confirmed Catherine’s suspicions, discovering “significant quantities of human remains” in a preliminary excavation. The remains, dated between 35 foetal weeks and three years old, were not from the famine period. This confirmation galvanized survivors and relatives, like Anna Corrigan, who had only learned in her 50s that her mother had given birth to two boys, John and William, at the home. While John’s death certificate listed “congenital idiot” and “measles” as the cause, William’s whereabouts remained unknown. Anna’s discovery underscores the profound pain of loss and the desperate need for closure for countless families who never knew the fate of their loved ones.

The ongoing excavation, led by Daniel MacSweeney, who has experience in recovering bodies from conflict zones, is a complex and sensitive operation. The tiny size of infant remains, often no larger than an adult’s finger, presents significant challenges in identification. MacSweeney emphasizes the meticulous care required to maximize the chances of identifying the remains, acknowledging the immense difficulty that cannot be underestimated. For families like Anna’s, who are still searching for answers about sisters, brothers, uncles, and aunts they never had the chance to meet, this painstaking process offers a glimmer of hope for closure and remembrance.

The discovery in Tuam has brought to the forefront the broader controversy surrounding Ireland’s mother and baby homes. Numerous reports and investigations have since shed light on the systemic failures and the profound suffering endured by mothers and children in these institutions. The ongoing excavation in Tuam is not just about unearthing physical remains; it is about acknowledging the past, honoring the memory of the lost children, and providing a measure of solace to the survivors who have campaigned tirelessly for the truth.

The story of Tuam is a stark reminder of the importance of transparency, remembrance, and the pursuit of justice for historical wrongs. As the excavation continues, the nation waits, hoping for answers and a final, respectful accounting for the hundreds of lives lost in this tragic secret.

Post Comment